|

|

|

|

|

eCysticFibrosis Review VOLUME 5, ISSUE 5 eCysticFibrosis Review VOLUME 5, ISSUE 5

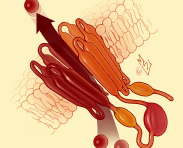

Improving digestive capabilities in nutritionally compromised patients with CF

In this Issue...

In this issue, we describe how nutrition in patients with CF affects common morbidities and overall mortality in this disease. New research reviewed includes:

- The role of early testing for exocrine pancreatic insufficiency using fecal elastase measurements over the first year of life

- The role of early nutrition status on long-term outcomes, including lung infection, and how this may be affected by pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy dosing

- Evidence for how many calories through supplementation are required to improve nutritional status

- How impaired small intestinal alkalization in patients with CF, in conjunction with delayed small intestinal transit, presents in the context of pancreatic enzyme activation and function

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

After participating in this activity, the participant will demonstrate the ability to:

|

|

Correlate exocrine pancreatic insufficiency with its effects on nutritional status. |

|

|

|

Describe strategies to improve nutritional status in patients with pancreatic insufficiency. |

|

|

|

Identify patients with inadequate response to pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy.

|

The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine takes responsibility for the content, quality, and scientific integrity of this CME activity.

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

IMPORTANT CME/CE INFORMATION

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

accreditation

statements

This activity has been planned and implemented in accordance with the accreditation requirements and policies of the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education (ACCME) through the joint providership of Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine and the Institute for Johns Hopkins Nursing. The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine is accredited by the ACCME to provide continuing medical education for physicians.

credit

designations

Physicians

Newsletter: The Johns Hopkins University School

of Medicine designates this enduring material

for a maximum of 1.0 AMA PRA Category

1

Credit(s)™. Physicians should claim only the credit commensurate with the extent of their participation in the activity.

Nurses

Newsletter: This 1 contact hour Educational Activity

is provided by the Institute for Johns

Hopkins Nursing. Each Newsletter carries a maximum of 1 contact hours or a total of 7 contact hours for the seven newsletters in this program.

Respiratory Therapists

For United States: Visit

this page to confirm that your state

will accept the CE Credits gained through

this program.

For Canada: Visit

this page to confirm that your province

will accept the CE Credits gained through

this program.

intended

audience

This activity has been developed for pulmonologists, pediatric pulmonologists, gastroenterologists, pediatricians, infectious disease specialists, respiratory therapists, dieticians, nutritionists, nurses, and physical therapists.

There are no fees or prerequisites for this activity.

launch date

This program launched on November 12, 2014 and is published monthly; activities expire two years from the date of publication.

hardware & software requirements

Pentium 800 processor or greater, Windows 98/NT/2000/XP or Mac OS 9/X, Microsoft Internet Explorer 5.5 or later, Windows Media Player 9.0 or later, 128 MB of RAM Monitor settings: High color at 800 x 600 pixels, Sound card and speakers, Adobe Acrobat Reader.

disclaimer

statement

The opinions and recommendations expressed by faculty and other experts whose input is included in this program are their own. This enduring material is

produced for educational purposes only. Use of Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine name implies review of educational format design and approach. Please review the complete prescribing information of specific drugs or combination of drugs, including indications, contraindications, warnings and adverse effects before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

Statement of Need

Based on a review of the current literature, including national and regional measures, detailed conversations with expert educators at Johns Hopkins, and a survey of potential program participants, this program will address the following core patient care gaps:

| Disease-Modifying Therapies |

| • |

Clinicians need guidance in understanding how new findings describing CFTR-modifying therapies may improve their treatment of patients with cystic fibrosis. |

| • |

Incomplete clinician awareness of genotype/phenotype correlations in non-pulmonary targets of CFTR-modifying therapies may limit their ability to provide optimal patient care. |

| Nutrition |

| • |

Clinicians lack effective guidance to increase caloric intake in patients who are nutritionally compromised. |

| • |

Clinicians do not fully understand how to manage the complexities of pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy to achieve optimal results in their patients. |

| Pseudomonas Aeruginosa |

| • |

Clinicians have unanswered questions about P. aeruginosa eradication in asymptomatic patients with positive cultures. |

| • |

New data and new choices for selecting initial inhaled anti-pseudomonal agents have created confusion. |

| • |

Conflicting data about pulmonary exacerbations has led to incorrect clinical assumptions and inappropriate treatment regimens. |

planner

disclosure

As a provider approved by the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education (ACCME), it is the policy of the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine Office of Continuing Medical Education (OCME) to require signed disclosure of the existence of financial relationships with industry from any individual in a position to control the content of a CME activity sponsored by OCME.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Members of the Planning Committee are required to disclose all relationships regardless of their relevance to the content of the activity. Faculty are required to disclose only those relationships that are relevant to their specific presentation. The following relationships have been reported for this activity:

Michael P. Boyle, MD, FCCP, discloses that he has served on scientific advisory boards for Gilead Sciences, Inc, Genentech, Vertex Pharmaceuticals Incorporated, and Savara. He has also served as Principal Investigator for Vertex Pharmaceuticals.

No other planners have indicated that they have any financial interests or relationships with a commercial entity.

Guest

Author's Disclosures

This activity is supported by educational grants from AbbVie, Gilead Sciences, Inc, and Vertex Pharmaceuticals Incorporated.

SUCCESSFUL COMPLETION

To successfully complete this activity, participants must read the content, and visit the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine's CME website and the Institute for Johns Hopkins Nursing. If you have already registered for other Hopkins CE programs at these sites, simply enter the requested information when prompted. Otherwise, complete the registration form to begin the testing process. A passing grade of 70% or higher on the post-test/evaluation is required to receive CE credit.

statement

of responsibility

The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine takes responsibility for the content, quality and scientific integrity of this CME activity.

CONFIDENTIALITY DISCLAIMER FOR CME CONFERENCE ATTENDEES

I certify that I am attending a Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine CME activity for accredited training and/or educational purposes.

I understand that while I am attending in this

capacity, I may be exposed to "protected health information," as that term is defined and used in Hopkins policies and in the federal HIPAA privacy regulations (the "Privacy Regulations"). Protected health information is information about a person's health or treatment that identifies the person.

I pledge and agree to use and disclose any of this protected health information only for the training and/or educational purposes of my visit and to keep the information confidential. I agree not to post or discuss this protected health information, including pictures and/or videos, on any social media site (e.g. Facebook, Twitter, etc.), in any electronic messaging program or through any portable electronic device.

I understand that I may direct to the Johns Hopkins Privacy Officer any questions I have about my obligations under this Confidentiality Pledge or under any of the Hopkins policies and procedures and applicable laws and regulations related to confidentiality. The contact information is: Johns Hopkins Privacy Officer, telephone: 410-735-6509, HIPAA@jhmi.edu

"The Office of Continuing Medical Education at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, as provider of this activity, has relayed information with the CME attendees/participants and certifies that the visitor is attending for training, education and/or observation purposes only."

For CME Questions, please contact the CME Office

(410) 955-2959 or e-mail cmenet@jhmi.edu.

For CME Certificates, please call (410) 502-9634.

Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine Office of Continuing Medical Education

Turner 20/720 Rutland Avenue

Baltimore, Maryland 21205-2195

Reviewed & Approved by:

General Counsel, Johns Hopkins Medicine (4/1/03)

(Updated 4/09 and 3/14).

internet

cme/ce policy

The Office of Continuing Medical Education (CME) at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine is committed to protecting the privacy of its members and customers. The Johns Hopkins University SOM CME maintains its Internet site as an information resource and service for physicians, other health professionals and the public.

Continuing Medical Education at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine will keep your personal and credit information confidential when you participate in a CME Internet-based program. Your information will never be given to anyone outside the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine's CME program. CME collects only the information necessary to provide you with the services that you request.

To participate in additional CME activities presented by the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine Continuing Medical Education Office, please visit www.hopkinscme.edu

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Planning Committee

Michael

P. Boyle, MD, FCCP

Associate Professor of Medicine

Director, Adult Cystic Fibrosis Program

Johns Hopkins University

Baltimore, MD

Peter

J. Mogayzel, Jr., MD, PhD

Professor of Pediatrics

Director, Cystic Fibrosis Center

Johns Hopkins University

Baltimore, MD

Donna

W. Peeler, RN, BSN

Pediatric Clinical Coordinator

Cystic Fibrosis Center

Johns Hopkins University

Baltimore, MD

Meghan Ramsay, MS, CRNP

Adult Clinical Coordinator

Cystic Fibrosis Center

Johns Hopkins University

Baltimore, MD

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

GUEST AUTHOR OF THE MONTH |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Commentary & Reviews: |

|

Steven Freedman, MD, PhD

Chief of the Division of Translational Research

Director, The Pancreas Center

Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center

Professor of Medicine

Harvard Medical School

Boston, MA

|

|

|

|

|

|

Guest

Faculty Disclosures

Dr. Steven Freedman has disclosed he has served as a consultant for and received grant funding from Alcresta.

Unlabeled/Unapproved Uses

Dr. Steven Freedman will not discuss any off-label or unapproved uses of any drugs or products.

Planning Committee Disclosures |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

TO COMPLETE

THE

POST-TEST

Step

1.

Please read the newsletter.

Step

2.

See the post-test link at the end of the newsletter.

Step

3.

Follow the instructions to access the post-test.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The initial descriptions of CF in the 1930s, culminating in the detailed clinical and pathological description of 49 affected infants by Dr. Dorothy Anderson, emphasized the critical role the exocrine pancreas plays in this disease.1 Pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy (PERT) is lifesaving, and subsequent articles have shown that nutritional status is strongly correlated with morbidities and survival in CF. However, achieving adequate nutrition has been challenging.

The causes of malnutrition can be viewed as an imbalance in energy metabolism. In an eloquent review published in 2000, Pencharz and Durie showed that patients with CF have a number of factors altering energy balance, including increased losses from intestinal, biliary, and pancreatic disease; decreased food intake; and increased energy needs as a result of infection and other inflammatory comorbidities combined with intrinsic CFTR cellular defects.2 The finding that pancreatic-insufficient patients with CF in Toronto placed on high fat diets survived longer (median age 30) than those on a low fat diet in Boston (median age 21), weighed more, and were taller controlling for mutational differences, led to a major change in nutritional recommendations.3 However, despite these findings, the majority of patients with CF remain malnourished. Efficacy of endogenous human pancreatic lipase is optimal at pH 8-9, but in the presence of bile salts, the pH optimum decreases to 6.0-6.5.4 Furthermore, efficient lipolysis is normally dependent on the presence of several different endogenous pancreatic lipases, including human pancreatic lipase 1 and 2, as well as carboxyl ester lipase (also referred to as bile salt-stimulated lipase), which is also expressed in breast milk. Furthermore, nonpancreatic sources of lipase, including those from the stomach and salivary glands, are important in the overall lipolytic process. Thus it is not surprising that porcine PERT is suboptimal.

The recent articles reviewed tackle a number of issues. O'Sullivan et al demonstrate that, in agreement with the original descriptions of CF and the rapid demise that would otherwise occur within the first several months of life due to malnutrition, there may already be extensive loss of exocrine pancreatic function in utero. It is intriguing to think that the low fecal elastase may not represent irreversible damage to the pancreas, with the fluctuations seen in some patients instead illustrating intermittent pancreatic ductal plugging and the opportunity to prevent further loss of pancreatic tissue. The advent of therapies targeting the CFTR protein itself (potentiators and correctors) may represent an opportunity to prevent exocrine pancreatic insufficiency and perhaps CF related diabetes mellitus (CFRD) in adulthood.

Yen et al extend prior observations that nutritional status affects the severity of lung disease and survival in patients with CF. Importantly, early nutrition in childhood is linked to improved lung function. This finding was borne out by studies showing that weight for age (WAP) > 50th percentile compared to < 50th percentile was associated with fewer acute pulmonary exacerbations and fewer hospitalization days at age 18, with a lower likelihood of having an impaired glucose tolerance test or CFRD. This would support data that newborn screening, leading to improved nutritional resuscitation early in infancy, has an impact on morbidities across the lifespan in an individual with CF. Based on these data, delay or episodes of suboptimal nutrition would be expected to have more far-reaching long-term health consequences.

How many calories is the optimal amount in a patient with CF? Similar to studies defining the minimum amount of normal CFTR function needed to prevent CF, Groleau et al demonstrate that one year supplementation of 114 kcal per day, on top of a 2500 kcal/day diet, had a substantial impact on growth and nutritional parameters as well as on resting energy expenditure. These studies, conducted in malnourished individuals at the approximately 30th percentile for height and weight, implicate this as a starting point but emphasize the need to target the 50th percentile—which is likely, although not proven, to further the health of our patients with CF.

Would this target be achieved with higher doses of PERT? In support of this statement, Haupt et al performed a CF Foundation Registry review and found that patients with CF on higher doses of PERT had a higher BMI. It cannot be concluded if PERT dosing directly affects BMI, but is highly likely. Since these patients were not on the highest dose of PERT recommended by the current guidelines, it may be that combining a very high fat diet (at least 100 gm/day) with 2,500 lipase units/kg/day could enhance BMI, decrease associated CF morbidities, and extend survival. Of note, patients in the highest BMI quartile were more likely to receive supplemental enteral feedings through nasogastric or gastrostomy tubes. More effective PERT preparations such as microbial-based lipases, including those used ex vivo for tube feedings, may be of further benefit.

Lastly, modifying the intestinal milieu may provide another therapeutic avenue. Lack of appropriate alkalization in the proximal small intestine, as shown by Gelfond et al, suggests that this plays a role not only in PERT efficacy, but also in understanding the underlying pathogenesis of impaired lipolysis and absorption of nutrients. In addition, wireless motility capsule studies may provide a rapid and robust means to assess efficacious therapies targeting nutrition, GI symptoms, and CFTR function.

Commentary References

1. Andersen DH. Cystic fibrosis of the pancreas and its relation to celiac disease: a clinical and pathological study. Am J Dis Child 1938; 56:344-399.

2. Pencharz P and Durie P. Pathogenesis of malnutrition in CF and its treatment. Clin Nutrition 2000; 19: 387-394.

3. Corey M, McLaughlin FJ, Williams M, Levison H. A comparison of survival, growth, and pulmonary function in patients with cystic fibrosis in Boston and Toronto. J Clin Epidemiol. 1988;41(6):583-591.

4. Fieker A, Philpott J, Armand M. Enzyme replacement therapy for pancreatic insufficiency: present and future. Clin Exp Gastroenterol. 2011;4:55-73.

|

|

| back

to top |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Evolution of pancreatic function during the first year |

|

|

|

|

O'Sullivan BP, Baker D, Leung KG, Reed G, Baker SS, Borowitz D. Evolution of pancreatic function during the first year in infants with cystic fibrosis. J Pediatr. 2013 Apr;162(4):808-812.e1.

(For non-subscribers to this journal, an additional fee may apply to obtain full-text articles.)

|

This 2013 publication reports on the first longitudinal study to examine serial fecal elastase values in infants with CF diagnosed through newborn screening. The goal was to define exocrine pancreatic function as a function of age and determine whether a fecal elastase value within the first 3.5 months of age predicted the value after 9 months. Sixty-one infants had fecal samples at these time points, with 53 individuals providing eight or more samples. The fecal elastase test was chosen based on: 1) its simplicity, since a small amount of a random stool is required; 2) lack of dependence on a 100 gram fat diet as required for the conventional fecal fat quantitative assay; and 3) lack of cross-reactivity with porcine pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy. The cut off value is < 200 µg/gm of stool, with values < 100 µg/gm of stool considered diagnostic of exocrine pancreatic insufficiency.

Twenty-nine infants had fecal elastase values < 50 μg/gm of stool, and all had values < 200 µg/gm at one year of age. An additional seven infants had initial values in the 50μg/gm to 100 μg/gm range. The 12 infants with initial values in the 100 µg/gm to 200 μg/gm range demonstrated greater variability in the values over time. Only four infants of this total of 48 infants with abnormal fecal elastase values demonstrated a value >200 micrograms/gram at one year.

Of the 13 infants with normal values > 200 μg/gm, 10 of 13 (77%) had normal results at the end of the study. Five of these 13 infants had a genotype consistent with pancreatic insufficiency.

Taken together, the results from this article demonstrate the initial fecal elastase values can show significant variability over the first year of life and thus may not be diagnostic of eventual exocrine pancreatic insufficiency. Normal values before 3.5 months of age generally reflected normal values after nine months of age. The authors recommend that abnormal values should prompt initiation of pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy, but follow-up fecal elastase testing be performed by one year of age to confirm the diagnosis of exocrine pancreatic insufficiency. This study highlights the importance of early diagnosis of exocrine pancreatic insufficiency using fecal elastase testing to initiate oral pancreatic enzymes to maximize nutrition rather than wait for signs of malnutrition/malabsorption and associated increased morbidities related to CF.

It is postulated that the intrasubject variability in fecal elastase results may reflect "pancreatic plasticity" due to variable ductal plugging and inflammation of the gland in the setting of defective CFTR. The authors point out that there was no control group of healthy infants to validate this statement and determine whether this variation may be simply a normal aspect of infant growth. They state that intestinal mucosal inflammation in the duodenum may impair cholecystokinin signaling of the pancreas, thus decreasing pancreatic enzyme output and giving a falsely low and variable fecal elastase value. Another explanation for the fluctuations includes diet, although these infants were on the same formula diet for at least the first six months of life.

It is important to emphasize that fecal elastase is measured as a concentration. Thus, a diarrheal stool may lead to a falsely low fecal elastase value. As shown in 1996 by Amann, Bishop, and Toskes,1 there is poor specificity of fecal elastase testing, with five of seven adult subjects with nonpancreatic diarrhea having fecal elastase values < 200 μg/gm of stool. With regard to intrasubject variability, Loser et al,2 who published the original studies examining fecal elastase testing in 1996, demonstrated an approximately 60% intrasubject variation in fecal elastase results with daily fecal elastase testing for 10 consecutive days in eight subjects. Thus, at least in adults, a value < 200 μg/gm of stool, may be normal the following day.

References

1. Amann ST, Bishop M, Curington C, Toskes PP. Fecal pancreatic elastase 1 is inaccurate in the diagnosis of chronic pancreatitis. Pancreas. 1996 Oct;13(3):226-230.

2. Löser C, Möllgaard A, Fölsch UR. Faecal elastase 1: a novel, highly sensitive, and specific tubeless pancreatic function test. Gut. 1996 Oct;39(4):580-586.

|

|

| back

to top |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Impact of nutritional status in childhood on clinical outcomes |

|

|

|

|

Yen EH, Quinton H, Borowitz D. Better nutritional status in early childhood is associated with improved clinical outcomes and survival in patients with cystic fibrosis. J Pediatr. 2013 Mar;162(3):530-535.

(For non-subscribers to this journal, an additional fee may apply to obtain full-text articles.) |

|

Several epidemiological studies have implicated the benefits of better nutritional status on improved lung function as assessed by FEV1 percent predicted. Specifically, nutritional status early in life, expressed as weight for height percentiles in children under age 2 and BMI for patients age 2 to 20 years, was associated with a higher FEV1 later in life. This article describes a prospective observational study of data taken from the CFF registry for patients with CF born between 1989 and 1992. The data from 3,142 patients were examined in order to evaluate the impact of nutritional status early in life on timing and velocity of height growth, lung function, complications of CF, and survival.

The authors stratified weight for age (WAP) at age 4 (the peak in the CF population) by quartiles: < 10th percentile, 10th–24th, 25th–49th, and 50th or greater. Complications examined included the number of flares and days hospitalized for pulmonary exacerbations, impaired glucose tolerance tests, CF-related diabetes (CFRD), and survival.

It was found that WAP predicted height throughout life. WAP < 10th percentile was associated with a lower FEV1 compared to all other WAP groups and never reached FEV1 > 80 percent predicted. However, the rate of decline in FEV1 was the same across the groups. The overall survival was 91% with 294 deaths during the observational period.

Examination of complications revealed that WAP > 50th percentile compared to < 50th percentile was associated with fewer acute pulmonary exacerbations and fewer hospitalization days at age 18, with no difference in the Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection rate (61.7%-66.9%). WAP > 50th percentile was associated with a lower likelihood of having an abnormal glucose tolerance test or CFRD.

Taken together with prior publications, these data show a strong connection between early nutritional status as assessed by WAP and subsequent impact on morbidities and mortality specific to CF. The reason for poor nutritional status is multifactorial in CF1 and includes increased losses by intestinal, pancreatic, and biliary derangements leading to maldigestion and malabsorption; decreased intake as a result of gastrointestinal symptoms, psychogenic, and iatrogenic causes; increased energy expenditure due to lung disease or infections; and perhaps increased resting energy expenditure as a result of CFTR cellular defects. Although the current study shows a strong association, there was not stratification by exocrine pancreatic status (although that is unlikely to be a major factor in the results obtained). Additionally, the impact of other modifier genes to improve growth and minimize organ disease cannot be ruled out.

However, this article extends prior observations indicating that if we can maximize nutritional support, patients are likely to improve outcomes later in life. The data from prior studies that early malnutrition is associated with a fivefold increased risk of diabetes would be consistent with the results seen in this study for glucose tolerance tests and CFRD. Building upon the results in the article by O'Sullivan et al described above – emphasizing early fecal elastase testing to inform initiation of pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy – it appears that enhancing nutrition beginning in the first year of life may have a significant long-term health impact.

References

1. Pencharz P and Durie P. Pathogenesis of malnutrition in CF and its treatment. Clin Nutrition 2000;19: 387-394

|

|

| back

to top |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Effect of Pancreatic Enzymes on Nutritional Outcomes

|

|

|

|

|

Haupt ME, Kwasny MJ, Schechter MS, McColley SA. Pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy dosing and nutritional outcomes in children with cystic fibrosis. J Pediatr. 2014 May;164(5):1110-1115.e1.

|

|

Building on the concept that nutritional status affects outcomes in patients with CF, this study examined whether pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy (PERT) dose dictates BMI. There is a wide variation in in PERT dosing, in part related to compliance. Although PERT was thought to be safe, the several case reports of fibrosing colonopathy in patients with CF who consumed very high doses of PERT led to the recommendation of an upper limit of 10,000 lipase units/kg/day or 2,500 lipase units/kg/meal.

The goal of this study was to determine whether PERT dose correlated with adjusted mean BMI percentiles. The authors analyzed 42,561 patient visits of 14,482 patients from 179 programs in the CF Foundation Registry from January 1, 2005 – December 31, 2008 and the highest PERT doses were recorded. The number of patients in the top and bottom BMI quartiles was 3,475 and 3,205, respectively. After adjustment for multiple covariates including age, race, ethnicity, FEV1 percent predicted, acid blocker use, presence of pseudomonas, nutritional supplement use, growth hormone therapy, and CFRD, the top BMI quartile demonstrated a higher lipase median dose (1,755 lipase units) per meal compared to 1,628 lipase units in the lowest quartile BMI group.

Although those results suggest that higher lipase doses may improve BMI, several caveats may suggest alternative explanations. Programs with the highest BMIs had more patients diagnosed through newborn screening (which has been shown to be linked to better nutritional outcomes), had higher FEV1 percent predicted, and were more likely to use nasogastric supplemental feeds and gastrostomy tube feeds with fewer receiving total parenteral nutrition. This group also had higher acid blocker use. The lowest quartile programs were associated with a higher frequency of CFRD, chronic insulin use, and osteoporosis. It should also be emphasized that the maximum lipase daily of 2,500 lipase units/kg/meal was not attained. That said, the difference of 127 lipase units between the top and bottom BMI quartile groups may be sufficient over time to enhance BMI. Further studies are needed to determine whether maximum PERT dosing improves nutritional outcomes.

|

|

| back to top |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Dietary interventions on growth and energy expenditure |

|

|

|

|

Groleau V, Schall JI, Dougherty KA, et al. Effect of a dietary intervention on growth and energy expenditure in children with cystic fibrosis. J Cyst Fibros. 2014 Sep;13(5):572-578.

|

|

Despite optimizing pancreatic enzyme therapy while maintaining a 100 gm fat diet, many patients with CF continue to be malnourished. This 12-month study examined whether supplementation with LYM-X-SORB, a lysophosphatidylcholine-rich structured lipid matrix, improved nutritional parameters compared to placebo (matched for calories) in children with CF. This randomized, double blind trial enrolled 70 children, with 52 providing completed analyzable data.

There were no significant differences between the groups, with a median added total caloric intake of 114 kcal/day after adjusting for adherence. At baseline, these children had suboptimal growth and nutritional status, as well as mild lung disease. Resting energy expenditure (REE) was elevated at baseline at 108.5%, decreasing to 106.5% at the end of 12 months. There was a concomitant improvement in growth status and muscle stores. The decrease in REE was seen only in males, which is consistent with the poorer outcomes observed for females with CF following puberty. However, the fact that REE has been shown to decrease over a one year period in pancreatic-insufficient patients with CF suggests that the supplementation in the current study prevented the drop in baseline levels in females with CF.

The demonstration that an additional 114 kcal/day led to improved growth and nutritional parameters has important ramifications. First, it provides a target for caloric supplementation. In the current study, the additional 5 percent caloric daily intake was linked to a clinically meaningful increase in weight for age (WAZ) and height for age (HAZ) scores, reflected by an improvement from the 31st to the 35th percentile in WAZ and for muscle scores improving from the 28th to the 38th percentile over one year. Secondly, this additional caloric intake of 114 kcal/day in patients who were consuming a median of 2,502 kcal/day indicates that 5 percent additional calories is sufficient to decrease REE in males and prevent an increase in females. Thus we now have defined supplemental caloric target values that will lead to improvements in nutritional parameters in malnourished children with CF.

|

|

| back

to top |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Implications of altered intestinal pH and transit on absorption |

|

|

|

|

| Gelfond D, Ma C, Semler J, Borowitz D. Intestinal pH and gastrointestinal transit profiles in cystic fibrosis patients measured by wireless motility capsule. Dig Dis Sci. 2013 Aug;58(8):2275-2281. |

|

|

|

In addition to optimizing PERT dosing, the enzymatic activity of PERT therapy may be affected by pH, luminal viscosity, and contact time with chyme. CF is characterized by a lack of neutralization of gastric contents as they enter the duodenum due to insufficient bicarbonate production by duodenal mucosal cells, as well as from pancreaticobiliary secretions. This lack of neutralization would be expected to: 1) impair dissolution of the enteric coating of PERT (optimum is pH 5.5-6.0); 2) decrease micelle formation; and 3) decrease mucus unfolding, leading to increased viscosity that affects mucosal integrity, nutrient assimilation, and small intestinal bacterial overgrowth.

Using a wireless motility capsule to measure in vivo pH and transit times, 10 patients with CF who were pancreatic-insufficient and not on acid-blocker therapy were compared to 10 healthy control subjects. Individuals were given a standardized low fat meal bar with PERT along with water and the wireless capsule. Compared to healthy controls, a lack of alkalization of the small intestine was confined to the initial 20 minutes of small bowel transit in CF subjects.

This was associated with a delay in the overall small bowel transit in CF patients by 2.3 hours compared to the healthy control group. Gastric emptying, colonic and whole gut transit times were not different.

These data have important implications. First, the results suggest that the lack of neutralization of gastric acid within the duodenum would impair the release and perhaps the optimal activation of porcine pancreatic enzymes. Because porcine enzymes are not as effective as our native enzymes, in particular with regard to lipase activity, this would be expected to further compromise digestion of triglycerides from the diet. If true, acid blockade with H2 blockers, and especially with proton pump inhibitors, should correct this issue. Although there may be some effect of acid blocker therapy on nutrient absorption, the effect is variable and not very profound both clinically and based on CFA measurements. Thus other factors must be at play to affect digestion of chyme in the proximal small bowel and may include altered viscosity due to improper unfolding of mucus, quantitative and qualitative alterations in bile, and/or alterations in the intestinal epithelial factors, including brush border enzymes. The delay in small bowel transit times in patients with CF would be expected to enhance nutrient absorption, but this does not appear to be the case and may lead to alterations in the microbiome and mixing at the villi surface.

Another important result from this study is that these derangements in pH neutralization and altered transit times within the small bowel as measured by wireless motility capsule may serve as robust outcome measures of dysfunctional CFTR. Use of this relatively noninvasive measurement could be of benefit for rapidly assessing the efficacy of newer CF therapies (including potentiators such as ivacaftor) for patients not only with the G551D mutation, but for testing this drug in patients with other mutation classes. Furthermore, this wireless capsule technology may facilitate rapid screening of pharmacologic therapies for the GI and nutritional manifestations of CF. |

|

| back to top |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

COMPLETE

THE

POST-TEST

Step

1.

Click on the appropriate link below. This will take you to the

post-test.

Step

2.

If you have participated in a Johns Hopkins on-line course,

login. Otherwise, please register.

Step

3.

Complete the post-test and course evaluation.

Step

4.

Print out your certificate.

* (The post-test for the newsletter is 1 credit hour.)

Respiratory

Therapists

Visit

this page to confirm that your state will accept the

CE Credits gained through this program or click on the

link below to go directly to the post-test.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

©

2015 JHUSOM, IJHN and eCysticFibrosis Review

Presented by JHUSOM and IJHN in collaboration with DKBmed. |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Illustration

© Michael Linkinhoker |

|

|

|

|

|